Knowing how to properly use threads should be part of every computer science and engineering student repertoire. This tutorial is an attempt to help you become familiar with multi-threaded programming with the POSIX (Portable Operating System Interface) threads, or pthreads. This tutorial explains the different tools defined by the pthread library, shows how to use them, and gives examples of using them to solve real life programming problems.

Technically, a thread is defined as an independent stream of instructions that can be scheduled to run as such by the operating system.

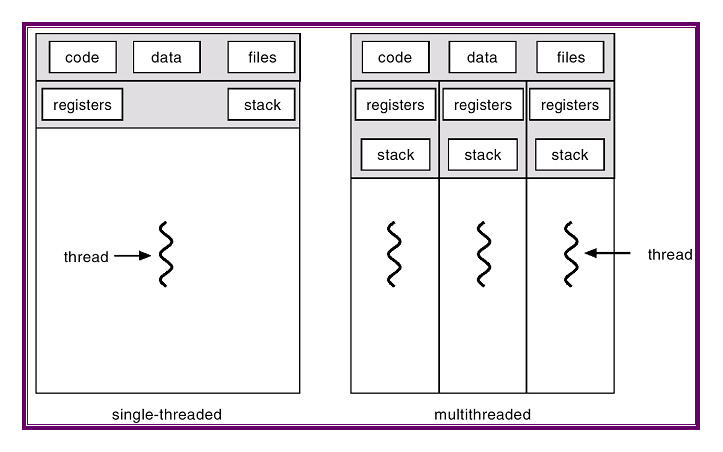

A thread is a semi-process that has its own stack, and executes a given piece of code. Unlike a real process, the thread normally shares its memory with other threads (where as for processes we usually have a different memory area for each one of them). A Thread Group is a set of threads all executing inside the same process. They all share the same memory, and thus can access the same global variables, same heap memory, same set of file descriptors, etc. All these threads execute in parallel (i.e. using time slices, or if the system has several processors, then really in parallel).

Single- and Multi-Threaded Processes

In order to take full advantage of the capabilities provided by threads, a standardized programming interface was required. For UNIX systems, this interface has been specified by the IEEE POSIX 1003.1c standard (1995). Implementations which adhere to this standard are referred to as POSIX threads, or Pthreads. Most hardware vendors now offer Pthreads in addition to their proprietary threads.

If implemented correctly, threads have some advantages over processes. Compared to the standard fork(), threads carry a lot less overhead.

Remember that fork() produces a second copy of the calling process. The parent and the child are completely independent, each with its own address space, with its own copies of its variables, which are completely independent of the same variables in the other process.

Threads share a common address space, thereby avoiding a lot of the inefficiencies of multiple processes.

On the other hand, because threads in a group all use the same memory space, if one of them corrupts the contents of its memory, other threads might suffer as well. With processes, the operating system normally protects processes from one another, and thus if one corrupts its own memory space, other processes won't suffer.

Example 1: A responsive user interface

One area in which threads can be very helpful is in user-interface programs. These programs are usually centered around a loop of reading user input, processing it, and showing the results of the processing. The processing part may sometimes take a while to complete, and the user is made to wait during this operation. By placing such long operations in a separate thread, while having another thread to read user input, the program can be more responsive. It may allow the user to cancel the operation in the middle.

Example 2: A graphical interface

In graphical programs the problem is more severe, since the application should always be ready for a message from the windowing system telling it to repaint part of its window. If it's too busy executing some other task, its window will remain blank, which is rather ugly. In such a case, it is a good idea to have one thread handle the message loop of the windowing systm and always ready to get such repain requests (as well as user input). Whenever this thread sees a need to do an operation that might take a long time to complete (say, more then 0.2 seconds in the worse case), it will delegate the job to a separate thread.

Example 3 : A Web server

When a multi-threaded program starts executing, it has one thread running,

which executes the main() function of the program. This is already a

full-fledged thread, with its own thread ID. In order to create a new thread,

the program should use the

pthread_create() function.

Here is how to use it:

#include <stdio.h> /* standard I/O routines */

#include <pthread.h> /* pthread functions and data structures */

/* function to be executed by the new thread */

void* PrintHello(void* data)

{

int my_data = (int)data; /* data received by thread */

pthread_detach(pthread_self());

printf("Hello from new thread - got %d\n", my_data);

pthread_exit(NULL); /* terminate the thread */

}

/* like any C program, program's execution begins in main */

int main(int argc, char* argv[])

{

int rc; /* return value */

pthread_t thread_id; /* thread's ID (just an integer) */

int t = 11; /* data passed to the new thread */

/* create a new thread that will execute 'PrintHello' */

rc = pthread_create(&thread_id, NULL, PrintHello, (void*)t);

if(rc) /* could not create thread */

{

printf("\n ERROR: return code from pthread_create is %d \n", rc);

exit(1);

}

printf("\n Created new thread (%u) ... \n", thread_id);

pthread_exit(NULL); /* terminate the thread */

}

Understanding the simple threaded program above. While it does not do anything useful, it will help you understand how threads work. Let us take a step by step look at what the program does.

main() we declare a variable called

thread_id, which

is of type pthread_t.

This is basically an integer used to identify the

thread in the system.

After declaring thread_id, we call the pthread_create

function to create a real, living thread.

pthread_create()

gets 4 arguments The first argument is

a pointer to thread_id, used by pthread_create()

to supply the program with the thread's identifier.

The second argument is used to set some

attributes for the new thread. In our case we supplied a NULL pointer to

tell pthread_create() to use the default values.

Notice that PrintHello() accepts a void * as an argument and

also returns a void * as a return value. This shows us that it is possible

to use a void * to pass an arbitrary piece of data to our new thread, and

that our new thread can return an arbitrary piece of data when it finishes.

How do we pass our thread an arbitrary argument? Easy. We use the fourth

argument to the pthread_create() call. If we do not want

to pass any data to the new thread, we set the fourth argument to NULL.

pthread_create() returns zero on success and a non-zero value

on failure.

pthread_create() successfully returns, the program will consist of

two threads. This is because the main program

is also a thread and it executes the code in the

main() function in parallel to the thread it creates.

Think of it this way: if you write a program that does not use POSIX threads

at all, the program will be single-threaded (this single thread is called

the "main" thread).

pthread_exit causes the current thread

to exit and free any thread-specific resources it is taking.

In order to compile a multi-threaded program using gcc,

we need to link it with the pthreads library. Assuming you have this library

already installed on your system, here is how to compile our first program:

The source code for this program may be found in the

hello.c file.

gcc hello.c -o hello -lpthread

pthreads in your Unix directory and copy and paste the code for

hello.c

into the pthreads directory. Compile the source code and ignore the casting warnings (the casts from int to void* and back to int are intentional here, and are used to pass an integer value to the thread function defined with a void * argument).

Run the

hello executable. The ouput should be similar to

Created new thread (4) ...

Hello from new thread - got 11

pthread_self(), which returns the thread id:

pthread_t pthread_self();

pthread_t tid;

tid = pthread_self();

hello.c to print out the thread id for both

threads. Make sure to use the format specifier %u (unsigned) to print out

the thread identifier. On Linux machines the thread identifiers are usually very large values that appear

to be negative if not interpreted as unsigned integers.

Recompile and run the hello executable.

The new ouput should be similar to

If you run your code on a Linux machine, the identifier of the new thread will be a very large integer rather than 4 (as shown here).

I am thread 1. Created new thread (4) ...

Hello from new thread 4 - got 11

Now modify the code so that the main thread passes its own thread id to the

new thread it creates. Recompile and run the hello executable.

The ouput should be similar to

I am thread 1. Created new thread (4) ...

Hello from new thread 4 - got 1

pthread_exit routine (the equivalent of exit for processeas). In this activity,

modify your hello.c program as follows.

PrintHello routine, add the line

sleep(1);before the

printf call. This causes the calling thread to sleep for 1 second and then resume execution (we are trying to make this thread finish after the main thread).

Use the Unix manual pages to find out what header files are needed for the sleep function (try manual entries 2, 3, etc. until you find the definition you need).

pthread_exit call.

hello

executable.

What happens? Why?

Next, add the pthread_exit call back in the main program, but remove

it from the PrintHello routine. Also add the sleep call

to the main routine, just before the second printf call, and remove

it from the PrintHello routine (so now the main thread finishes last). Recompile and run the hello

executable.

What happens? Why?

It is necessary to use pthread_exit at the end of the main program.

Otherwise, when it exits, all running threads will be killed.

pthread_join()

function for threads is the equivalent of wait for processes.

A call to pthread_join

blocks the calling thread until the thread with identifier equal to the first

argument terminates.

#include <stdio.h> /* standard I/O routines */

#include <pthread.h> /* pthread functions and data structures */

void* PrintHello(void* data)

{

pthread_t tid = (pthread_t)data; /* data received by thread */

pthread_join(tid, NULL); /* wait for thread tid */

printf("Hello from new thread %u - got %u\n", pthread_self(), data);

pthread_exit(NULL); /* terminate the thread */

}

/* like any C program, program's execution begins in main */

int main(int argc, char* argv[])

{

int rc; /* return value */

pthread_t thread_id; /* thread's ID (just an integer) */

int tid;

tid = pthread_self();

rc = pthread_create(&thread_id, NULL, PrintHello, (void*)tid);

if(rc) /* could not create thread */

{

printf("\n ERROR: return code from pthread_create is %d \n", rc);

exit(1);

}

sleep(1);

printf("\n Created new thread (%u) ... \n", thread_id);

pthread_exit(NULL);

}pthread_join() is the identifier of the thread to join.

The second argument is a void pointer.

pthread_join(pthread_t tid, void * return_value);

return_value pointer is non-NULL, pthread_join will place

at the memory location pointed to by return_value,

the value passed by the thread tid through the pthread_exit call.

Since we don't care about return value of the main thread, we set it to NULL.

Recompile and run the executable for the above code. Is the otuput what you expected?

Note. At any point in time, a thread is either joinable or detached (default state is joinable).

Joinable threads must be

reaped or killed by other threads (using pthread_join) in order to free memory resources.

Detached threads cannot be reaped or killed by other threads, and resources are automatically

reaped on termination. So unless threads need to synchronize among themselves, it is

better to call

instead of pthread_detach(pthread_self());

pthread_join.

hellomany.c

that will create a number N of threads specified in the command line, each of which

prints out a hello message and its own thread ID. To see how the execution of the

threads interleaves, make the main thread sleep for 1 second for every 4 or 5 threads

it creates. The output of your code should be similar to:

I am thread 1. Created new thread (4) in iteration 0...

Hello from thread 4 - I was created in iteration 0

I am thread 1. Created new thread (6) in iteration 1...

I am thread 1. Created new thread (7) in iteration 2...

I am thread 1. Created new thread (8) in iteration 3...

I am thread 1. Created new thread (9) in iteration 4...

I am thread 1. Created new thread (10) in iteration 5...

Hello from thread 6 - I was created in iteration 1

Hello from thread 7 - I was created in iteration 2

Hello from thread 8 - I was created in iteration 3

Hello from thread 9 - I was created in iteration 4

Hello from thread 10 - I was created in iteration 5

I am thread 1. Created new thread (11) in iteration 6...

I am thread 1. Created new thread (12) in iteration 7...

Hello from thread 11 - I was created in iteration 6

Hello from thread 12 - I was created in iteration 7More examples using the pthread library can be found

here.